Hebrews 5:5-10 New Revised Standard Version

5 So also Christ did not glorify himself in becoming a high priest, but was appointed by the one who said to him,

“You are my Son,

today I have begotten you”;6 as he says also in another place,

“You are a priest forever,

according to the order of Melchizedek.”7 In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission. 8 Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered; 9 and having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him, 10 having been designated by God a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek.

***************

In 1 Peter 2, we’re told that to be in Christ is to be part of a royal priesthood (1 Peter 2:9). That revelation led to the doctrine, especially prominent among Protestants, of the “priesthood of all believers.” The document that guides the ordering of ministry in my denomination—The Theological Foundations for the Ordering of Ministry in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)—speaks directly to this understanding of priesthood: “In Christ the individual becomes a member of ‘a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people of God’s own possession’ (1Peter 2:9). Thus it has been common to speak of the ‘priesthood of all believers’ —the persons who live as faithful disciples of Jesus Christ in the church and in the world. This language highlights the sacramentality of the work of the laity through whose witness and service the grace of God is made manifest.” If we are all part of this royal priesthood, who is the high priest? In the Book of Hebrews, we are told that Jesus is the high priest. Of course, there is a caveat here, and we’ll need to address it. That caveat has to do with the qualifications for being a priest and whether Jesus actually qualifies.

In ancient Israel, the priesthood was limited to the tribe of Levi, while the high priests were to be lineal descendants of Aaron. As for Jesus, he was neither a Levite nor a descendant of Aaron. So, how might he be our high priest? According to the genealogies in Matthew and Luke Jesus was a descendant of David, which made him a member of the tribe of Judah. That seeming barrier does stop the author of Hebrews from creating a workaround so that Jesus might qualify. While Jesus might not be a descendant of Aaron, Hebrews simply calls Jesus a priest according to the order of Melchizedek.

Before we get to this mysterious Order of Melchizedek, we would be wise to begin with the question of Jesus’ appointment to the office of high priest. Then we can turn to Melchizedek and the implications of this passage for our Lenten journey. The reading from Hebrews 5:5-10 is part of a larger section of the letter that begins in verse 14 of chapter 4. In the opening lines of the section, the author of Hebrews (Hebrews is anonymous) writes that “since, then, we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast to our confession.” We’re also told that this high priest can sympathize with our weaknesses. He was “tested as we are” and yet he did not sin. Therefore, we can “approach the throne of grace with boldness, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need” (Heb. 4:15-16).

Having learned about this high priest who was tested and yet without sin, when we come to verses 5-6 of chapter 5, we are told that when appointed to this position, Jesus did not glorify himself but was appointed to the position by God. Thus, the author draws upon the Psalms to describe the qualifications of this high priest. First, God says of this high priest, “you are my Son, today I have begotten you” (Ps. 2:7). So, the main qualification here is that Jesus is the Son of God. Then, we learn that Jesus is “a priest forever, according to the order of Melchizedek” (Ps. 110:4).

The author of Hebrews makes it clear that one does not appoint oneself to the position of high priest. In the verse prior to our passage, we read that “one does not presume to take this honor, but takes it only when called by God, just as Aaron was (Heb. 5:4). As noted above, Jesus did not descend from the priestly line, so Hebrews links him to the mysterious Melchizedek, who appears in Genesis as the priest-king of Salem who receives tithes from Abraham and blesses him (Gen. 14:17-20). This figure suddenly appears and then disappears from the story. But, the author of Hebrews discovers in this mysterious figure the means to unlock Jesus’ high priestly calling. He might not have an Aaronic pedigree, but he has something else, something rooted in mystery. Interestingly, it’s only in Hebrews that Jesus is connected to Melchizedek. But the identification of the too is intriguing.

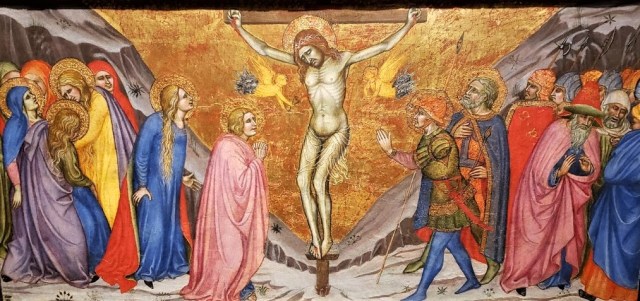

Having been appointed to this position as a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek by God, in large part because of his status as Son of God, Jesus takes up his priestly duties. During his earthly life, Jesus “offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death.” Here is a reference to Jesus’ priestly duties taken up, it would appear, while on the cross. He was heard because of his submission to the one who appointed him to this role. He was heard because of his submission. Though he held the status as Son of God, in words reminiscent of what Paul said of Jesus in Philippians 2—he “learned obedience through what he suffered.” It was in this suffering that he was perfected and became the source of our salvation. Nothing is said here about being a substitute sacrificed for our sins. The point simply is that his pathway to this priesthood of Melchizedek included the suffering of the cross.

Back in Hebrews 4, the author reveals that Jesus is not a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses. He too has been tested and yet did not sin (Heb 4:15-17). That testing includes suffering. Jesus can understand our struggles, our sufferings, because he also suffered. This is the foundation of his priesthood. You might say that he graduated from the school of hard knocks. This is true even though he was the Son of God. That status did not prevent him from experiencing human realities, therefore, we can put our trust in him. In this, we find good news.