Hebrews 9:24-28 New Revised Standard Version

24 For Christ did not enter a sanctuary made by human hands, a mere copy of the true one, but he entered into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf. 25 Nor was it to offer himself again and again, as the high priest enters the Holy Place year after year with blood that is not his own; 26 for then he would have had to suffer again and again since the foundation of the world. But as it is, he has appeared once for all at the end of the age to remove sin by the sacrifice of himself. 27 And just as it is appointed for mortals to die once, and after that the judgment, 28 so Christ, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin, but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him.

****

Like much of the New Testament, the Book of Hebrews has a strong apocalyptic element. We see that apocalyptic dimension present here in this passage. Because of how apocalyptic messages have been used over the centuries and especially over the past several decades, there is general discomfort with the apocalyptic dimension of the New Testament. It’s understandable. However, it’s there for all to see. We can’t ignore it. Besides the apocalyptic elements of the New Testament provide a certain intensity and alertness to the texts. It brings to the fore a certain anticipation that something is about to happen. Granted, we live two millennia later and, as of yet, Jesus hasn’t returned. That is why theologians such as Origen and Augustine allegorized texts like this. In fact, one scholar spoke of Origen demythologizing the apocalyptic elements. There is reason to do so. At the same time, it’s important that we not ignore the message even if we must reinterpret it.

First-century Christians expected Jesus to return at any moment. At times Paul encouraged such thinking and at other times he had to calm the folks down, reminding them that in the meantime they needed to attend to business. That is, go to work so you can eat. That being said, the author of Hebrews, whose identity remains unknown, offers us a meditation on the apocalyptic dimension of Jesus’ ministry.

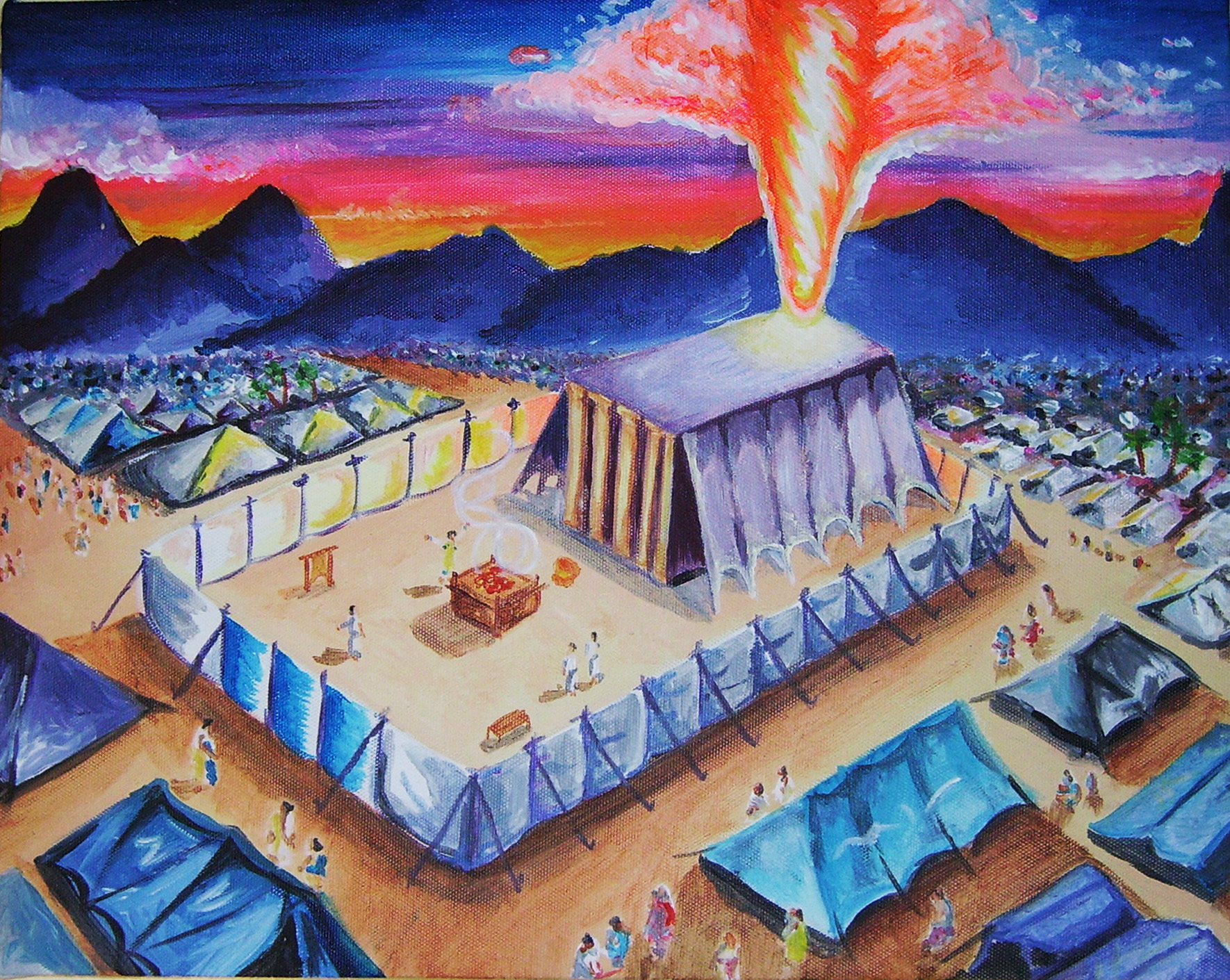

As noted in a previous reflection, Hebrews represents a Platonized vision of the ministry of Jesus. He contrasts the earthly ministry of the Levitical priesthood with Jesus’ heavenly priesthood. Whereas the Levitical priests had to annually offer sacrifices on behalf of not only the general populace but themselves as well. In our reading, which continues the messaging we’ve been hearing, Jesus enters the heavenly Temple ready to offer a sacrifice for sin. The sacrifice he offers is himself. Nothing is said here of the cross upon which Jesus died but is rather an offering of himself to God as a replacement for the annual sacrifices. That is, the author of Hebrews focuses on the sacrifices offered on the Day of Atonement and not Passover. While we know from Scripture (Leviticus 16) what this involves, the nature of the sacrifice on Jesus’ part is not revealed. In other words, the cross is not specifically mentioned.

The apocalyptic element is clear in the statement that Jesus has appeared “at the end of the age to remove sin by the sacrifice of himself.” The way it is phrased here, Jesus has already done this, suggesting that the “end of the age” has already occurred, and that it occurred when Jesus offered himself in the heavenly Temple in the presence of God on our behalf. In doing this, Jesus acted to remove sin from us. As noted elsewhere in Hebrews, Jesus does this only once and not annually as was true of the Levitical priests. As we’ve seen earlier, Jesus takes his priesthood from the mysterious line of the priest-king Melchizedek (Heb. 7).

The reading suggests that the end of the age began when Jesus offered himself up as the atoning sacrifice in the heavenly temple. In other words, what happened on earth with the crucifixion also happened in heaven as Jesus entered the heavenly Temple and offered himself up to God as an atoning sacrifice. This is the word Hebrews offers concerning the first advent, but there is a second as well. Some use the analogy of D-Day for understanding the cross. While the war would continue for almost a year in Europe, once the allies landed in Normandy the war was won. There would be no turning back. With that analogy as a reference to the cross, Jesus gained a beachhead that would never be turned back. There would be many more battles to come. Evil hasn’t given up its resistance, but it will not win. Even for those of us who believe that the future is open and unwritten, could we not say that Good Friday and Easter turned the tide?

Hebrews acknowledges that we all die once, and then comes the day of judgment. What this means is not clear, though Jürgen Moltmann cautions those of us who lean toward universal salvation,

If salvation is tied to faith, then all the universal statements in the New Testament must be related to God’s good salvific intention, but not to the outcome of history. What is meant is the possibility of redemption, not its inevitable actuality. It is true that the word aionios does not mean the absolute eternity of God, but it does mean the irrevocability of the decision for faith or unbelief. Faith’s experience that in the presence of the call to decision one is standing before God has as its corollary the finality of human decision. Consequently `the double outcome’ is the last word of the Last Judgment. [Moltmann. The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology (Kindle Locations 3506-3509). Kindle Edition].

That is good to remember—the outcome is not inevitable. We have choices and redemption can’t be coerced if God is truly love.

When it comes to the timing of this day of judgment, it does sound here as if it immediately follows death. Other passages of Scripture suggest a different timeframe, so unless we embrace a God who stands outside time (timeless) then we have some interpretive moves to make here. Whatever the time frame, the story is not yet complete. There is also a second coming. But unlike the first advent, in which Christ dealt with sin (apparently through his death on the cross) this second advent is designed to save the faithful who are eagerly awaiting Jesus’ return.

Hebrews doesn’t reveal exactly what is meant by the word “save,” but it would seem that the expectation is that Jesus will return to gather up the faithful bringing this age to a close. Judgment has already occurred, so the expectation is not one of fear but hope. Thus, salvation in this context is not related to deliverance from sin, but a gathering up of those whom Jesus has already saved. Tom Long puts it this way concerning the anticipated day of judgment:

In this part of the passage, the writer of Hebrews indicates that the offering of Christ makes this obsession with judgment moot. In Christ, sin has already been extinguished, and lasting forgiveness has been granted. So Christians do not have to dread the future, watching fearfully for God the judge. God’s future is one of salvation and redemption. Christ is “coming again,” not with a sword of judgment, but “to save those who are eagerly waiting for him.” [Long, Feasting on the Word, p.

283].

So, instead of putting up signs that call for people to get right with God, in Christ, we are already made right with God. So, we can focus on other things. Judgment day is not a day to be feared but celebrated. So keep alert, the day of the Lord is near at hand!! Maranatha! Lord Come Quickly!

| Image attribution: Icon of the Second Coming, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56666 [retrieved October 31, 2021]. Original source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Icon_second_coming.jpg. |

.jpg/766px-Abraham_meets_Melchisedech_(San_Marco).jpg)