Romans 8:12-17 New Revised Standard Version

12 So then, brothers and sisters, we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live according to the flesh— 13 for if you live according to the flesh, you will die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live. 14 For all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God. 15 For you did not receive a spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received a spirit of adoption. When we cry, “Abba! Father!” 16 it is that very Spirit bearing witness with our spirit that we are children of God, 17 and if children, then heirs, heirs of God and joint-heirs with Christ—if, in fact, we suffer with him so that we may also be glorified with him.

***********

We are children of God if we are led by the Spirit of God. Of course, our status as children of God is due to natural descent. We are not by nature divine. However, according to Paul, we are children of God by adoption. This adoption by God involves the indwelling of the Spirit. If we are adopted by God through the indwelling of the Spirit, that makes us Jesus’ siblings. And, apparently, this makes us joint-heirs with Jesus. It’s good to remember that in the ancient world the inheritance went to the first-born son. Everyone else was on their own unless the first-born decided to share. In this case, Jesus appears to have made that choice. We get to share in his largesse, which is an act of grace. That is Paul’s message to the Roman church.

The reading designated for Trinity Sunday takes us back to Romans 8, which provided the Second Reading for Pentecost Sunday. In the reading for the previous week (Romans 8:22-27), Paul writes that the Spirit of God intercedes on our behalf when we don’t have the words to offer in prayer. When we lack the words to speak to God, the Spirit can interpret our groans and our sighs, making known our concerns and requests. That ministry of the Spirit occurs because the Spirit of God indwells us. Not only does the Spirit interpret our sighs and groans, but the Spirit also, as we learn in today’s reading, enables us to call out “Abba, Father.” In this, we share a position in the family of God with our elder brother, Jesus the Christ.

We hear this word about our status as children of God on Trinity Sunday. At first glance, this is not a distinctively trinitarian passage. Yes, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are present, but the formula is a bit ad hoc. The nature of the relationship between the three persons is not explicitly stated. To get there we have to read the passage through a trinitarian lens. Being that I am by theological orientation trinitarian, I can do this, but it might not be obvious to everyone. If we can imagine the text through this lens, then what we see here is a word about relationships first within the nature of God and then between God and God’s people. As Clayton Schmidt writes, “the main thrust of this text is not so much to explicate Trinitarian theology as to draw Paul’s readers into the family of God.” [Feasting on the Word, p. 41]. So, if we read this through a trinitarian lens then the message here is that through adoption we are drawn into union with God, who is our parent by adoption through the Spirit, which makes us siblings of Jesus.

Perhaps the message here is really about belonging. We all want to belong to some form of family or community. Paul understands this, perhaps more intimately than we truly know, and so he speaks of a new kind of family, one that is thicker than blood. It is by adoption that we are drawn into this new family, but as God’s adopted children we can call out to God, just as Jesus did, speaking to God as “Abba! Father!” Ultimately, we can do this through the Spirit who calls out to God on our behalf (Rom. 8:22-27).

So, what does it mean to be adopted and therefore a joint heir with Jesus? As Kelley Nikondeha, who is herself and an adoptee with an adopted child, points out, how the ancient Greco-Roman world understood adoption differs markedly from how we understand it.

Our contemporary concept of adopting an infant, with the connotations of nurture, care, and compassion, is, in fact, anachronistic. The common understanding of adoption in the Greco-Roman world would have been functional: it was a tool of the elite (especially the emperors) to secure succession, legacy, and inheritance. Adopted sons were pulled into a bigger story and expected to fulfill an imperial purpose. In those times, adoption was about the coalescing and movement of power, not the rescue of orphans. [Adopted, p. 23].

This understanding of adoption is important in that it reminds us that Paul always has in mind the message is the son of God, not Caesar. While Caesar shores up power through adoption, God need not do this. However, Paul understands that by using this terminology he is reinforcing what it means to belong to God’s family. We get to share in that power given to Jesus, not by natural descent but through the choice made by the heir who draws us into the family through the Spirit.

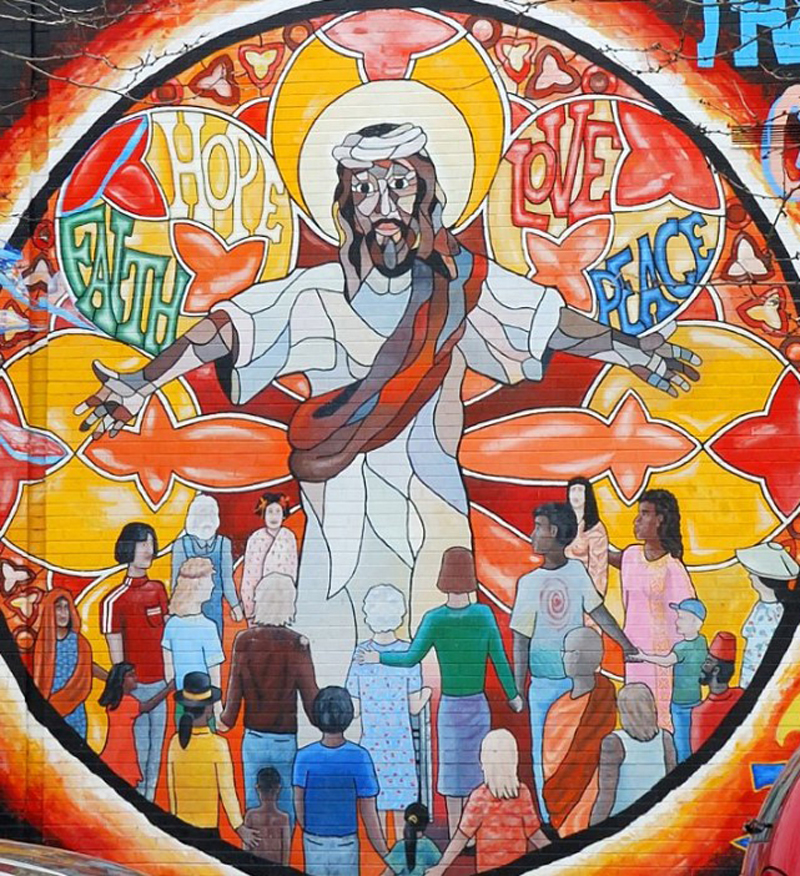

As Nikondeha points out, in Paul’s understanding of adoption, we’re not merely “imperial functionaries; we are also family members. As family, we recognize one another as siblings and are invited into filial solidarity as adopted ones.” [Adopted,p. 24]. That suggests that Paul is interested not only in our relationship with God but our relationships with each other. We are family. Therefore, we should be in solidarity with one another in a way that transcends DNA. In fact, this relationship that exists through the Spirit’s indwelling stands before the relationship defined by blood/DNA. For those who do not belong to a physical family, for whatever reason, they do belong to the family of God, with Jesus as the older brother who welcomes us all into the circle. So, again, drawing on Nikondeha’s writings on adoption: “As heirs, we participate in extending God’s kingdom of peace. As a family, we recognize others as siblings who ought to be treated as such. As adopted ones, we extend that magnanimous belonging to others” [Adopted, p. 27]. One more word from Nikondeha on adoption: She writes that “adoption imbues belonging with elasticity—we know there is always room for more at the table and more in the family. As we shape our own communities of belonging, we have to run to keep up with the divine largess, since God keeps growing his family with great creativity and an ever-greater reach” [Adoption, p. 28]. Is not that Paul’s message? One’s place in the family doesn’t depend on blood but grace.

If we are siblings of Jesus, and therefore, heirs of the promises of God, which includes our redemption, then does this not ultimately lead to union with God? In a trinitarian reading of this passage, we can join with Eastern Christians in imagining how the Son became incarnate, bringing together humanity and divinity. To be in Christ, allows us to share in that reality, what Eastern Christians call theosis or deification. As Gregory Palamas shared in a sermon “Heaven is open to them to receive them in due course if, increasing in faith in God and righteousness according to faith, they receive power to become heirs of God and joint-heirs with Christ, sharing in His incorruptible life and immortality, inseparably united with Him and enjoying His glory (Rom. 8:17–18).