8 Owe no one anything, except to love one another; for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law. 9 The commandments, “You shall not commit adultery; You shall not murder; You shall not steal; You shall not covet”; and any other commandment, are summed up in this word, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” 10 Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law.

11 Besides this, you know what time it is, how it is now the moment for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we became believers; 12 the night is far gone, the day is near. Let us then lay aside the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; 13 let us live honorably as in the day, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarreling and jealousy. 14 Instead, put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires.

We encounter this reading from Romans 13 amid difficult times, when politics, pandemic, and racial unrest have mixed. The verses just before our reading, verses not included in this lectionary cycle, encourage the readers to subject themselves to the political authorities because they have been instituted by God. Once upon a time, this passage was the foundation of the theory of divine right monarchy. In the seventeenth century, an alternative view of this emerged that was connected to figures such as John Locke that declared that the voice of the people was the voice of God. We still struggle to make sense of those verses. That passage ends with Paul telling the Romans to pay their taxes and give honor and respect to those to whom it is due. I’ve cut my scholarly teeth on advocates of divine right monarchy, but my political allegiance leans toward the “Vox Populi, Vox Dei” position. But that’s really not the focus of our reading for Labor Day Weekend, for Paul turns the tables a bit and tell us to “owe no one anything, except to love one another.” If we do this, then we fulfill the law—not the law of the land, but the law of God, which transcends the law of the land. To fulfill the law of love is to fulfill all law.

Paul makes the point, which I’ve long held, that if we fulfill the command to love our neighbors, then we fulfill the second table of the Law. If you love your neighbor you won’t commit adultery, commit murder, steal, covet, or as Paul says, break any other of the commands. That’s because “love does no wrong to a neighbor.” I wonder, how does this declaration fit with what went before? Paul seems to want the people who form the church to live in such a way that their behavior serves as a witness to Christ. Paul isn’t naïve. He understands the world in which he lives. He knows that the ways of Rome aren’t the ways of God’s realm. He also understands that the Jesus Movement is a small community, and so it has to navigate these realities as best they can. What they can do, however, is give evidence of the law of love. This, by itself, is subversive. Rome understands power, and its definition involves brute force.

From the command to love, Paul moves into an eschatological mode, urging the readers to wake up to the moment of salvation, which is near at hand. We must remember that Paul has an apocalyptic perspective, believing that the realm of God will break in quickly, which would mean that the days of Rome’s hegemony were numbered. They were living through the darkness that is night, but the day is about to dawn. The contrast between light and darkness, night and day are prominent images in the New Testament. We see this especially in the Johannine literature, but also in Paul’s letters. In the ancient world, when a candle might be the only source of light, except on a moonlit night, people feared the darkness. Things went bump in the night, so you waited for dawn to break. In Paul’s mind it wasn’t fear of demons in the night, but rather his anticipation that day is about to dawn. So, it’s time to wake up and get ready for the coming of the Lord.

In our day of racial polarization, the images of light and darkness have taken on a problematic dimension. Light has been equated with whiteness, and thus light/white is understood to be good. This is unfortunate because the imagery has great power if we can remove the racialized elements. For Paul the dawn is near, and with it comes salvation in Christ. Paul encourages the readers to live honorably as in the day, and put aside the markings of the nightscape, such as reveling and drunkenness, debauchery and licentiousness, quarreling and jealousy. These are the activities of the night when good people should be at home in bed.

So, “put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires.” Paul often speaks of the “flesh,” by which he isn’t thinking of the body itself, but the ways of the world that stand opposed to the things of God. Remember that in chapter 12, Paul urges believers to offer their bodies to God as a living sacrifice. He tells them not to be conformed to this world, but to be transformed by the renewing of their minds (Rom. 12:1-2). So, when he speaks of “making no provision for the flesh” he’s thinking in terms of conforming to the patterns of this present age. As proof positive, all that his readers needed to do was look around to see what was happening in the city of Rome. Yes, obey the authorities, but don’t follow the adage that “when in Rome do as the Romans do!” Instead “let love be genuine; hate what is evil, hold fast to what is good” (Rom. 12:9). That is, put on Christ, by that Paul means giving allegiance to Christ. If we read this in light of the opening verses of chapter 13, Paul has placed the Roman authorities in their proper place, as subservient to the realm of God.

It is wise to heed these words at this moment in time when it is easy for us to get wrapped up in the political realm as if our political parties are ultimate. They have their place, but they are not Christ. To replace Jesus with the flag is idolatry.

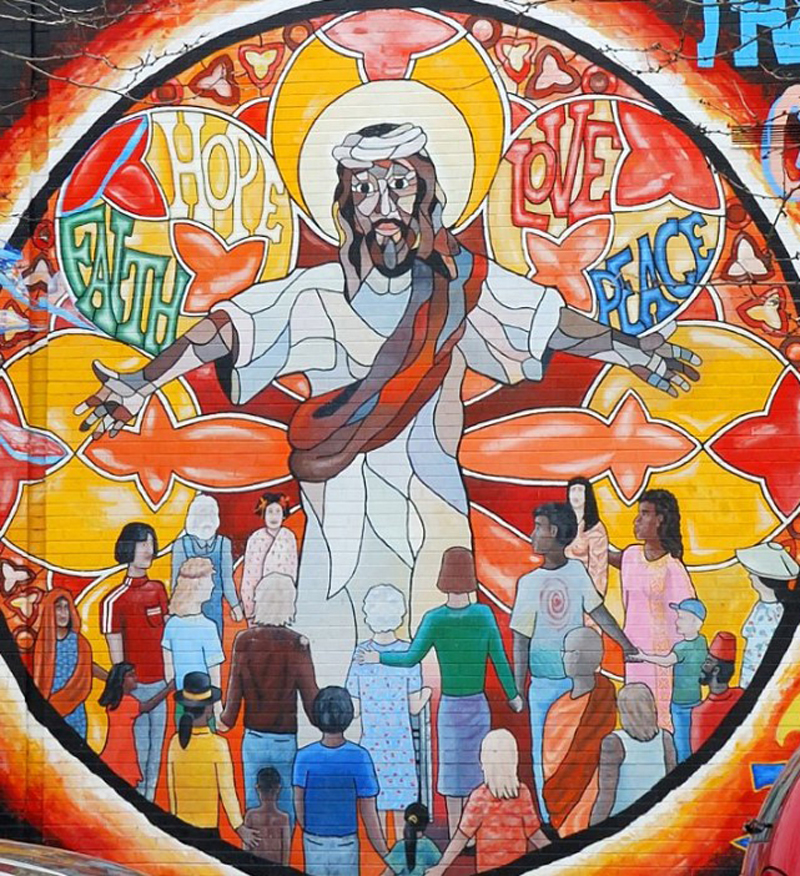

Image Attribution: Jesus Mural of Faith, Hope, Love, and Peace, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56412 [retrieved August 29, 2020]. Original source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/36847973@N00/3342340183.