13 Now who will harm you if you are eager to do what is good? 14 But even if you do suffer for doing what is right, you are blessed. Do not fear what they fear, and do not be intimidated, 15 but in your hearts sanctify Christ as Lord. Always be ready to make your defense to anyone who demands from you an accounting for the hope that is in you; 16 yet do it with gentleness and reverence. Keep your conscience clear, so that, when you are maligned, those who abuse you for your good conduct in Christ may be put to shame. 17 For it is better to suffer for doing good, if suffering should be God’s will, than to suffer for doing evil. 18 For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, 19 in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, 20 who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. 21 And baptism, which this prefigured, now saves you—not as a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, 22 who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers made subject to him.

How do we live faithfully in challenging times? In other words, how does our Christian faith guide our actions when we face challenges? As I write this we are experiencing a pandemic that has shut down most of the world’s economies. Most of us are sheltering-in-place to reduce the spread of a deadly virus because we lack an effective treatment or vaccine. There are those, of course, who in the name of religious freedom are declaring their immunity from all government requirements or advisements (such as not having in-person worship services). This is our situation as we read this passage from 1 Peter. The communities to which this letter is written (whether by Peter or someone using his name) are experiencing some form of distress or suffering. They may be struggling to find answers, but Peter wants them to stay strong, stay focused, and live faithfully.

We pick up this reading from 1 Peter for the Sixth Sunday of Easter. The reference in verses 21-22 speaks of resurrection and ascension, making this a truly Easter text. The reading as a whole continues a conversation about how one should behave as a Christian and how that behavior demonstrates the truth of one’s confession of faith in the risen Christ. As part of this conversation, Peter introduces what is known as the “household code.” In the first century, this code made complete sense. It reflected societal norms. Today we find them problematic at best. Nevertheless, Peter speaks to three forms of relationship: family life, slavery, and the relationship of the Christian to the state. Wives are encouraged to submit to their husbands (embracing patriarchy), Slaves are instructed to obey their masters (one would assume that a large number of early Christians were slaves, who are instructed to grin and bear their condition in the expectation of an eternal reward). Finally, Peter encourages the people to honor the emperor and submit to the governing authorities who are authorized to punish evil and praise what is good. This instruction suggests that widespread requirements to offer sacrifices to the emperor had yet to take full force. Nevertheless, the point here is related to Peter’s reminder that they are aliens and exiles. Therefore, he encourages them to ”conduct yourselves honorably among the Gentiles, so that, though they malign you as evildoers, they may see your honorable deeds and glorify God when he comes to judge” (1 Peter 2:11-12). It is also worth noting that these congregations likely were made up largely of people who were slaves whose masters were likely pagans and wives whose husbands might be pagans. So, be careful with how you live, because your life in Christ will set you apart.

While the lectionary creators may have omitted the “household codes,” they are an important part of the story. We needn’t embrace them, but it is helpful to take of them to understand their condition. They are already under suspicion, so don’t rock the boat any further than had to. Perhaps we can learn something from these instructions about living in ways that give a good witness to the gospel that reflect the changing dynamics of modern life.

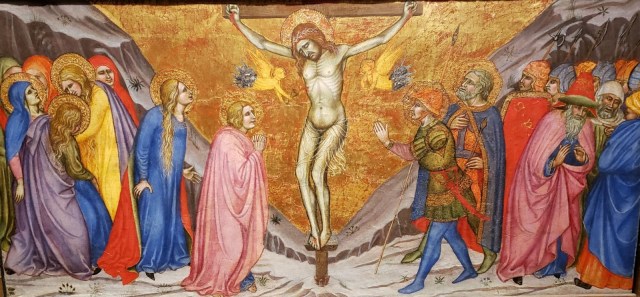

So, do what is right. Fear God (reverence God) but don’t fear human persecutors. If you suffer, then suffer for what is right and good. Then when asked, give a defense of your faith. Share why you are a follower of Jesus. I don’t think Peter has in mind a theological dissertation. He is not suggesting that one explain each of the finer points of the Nicene Creed or Paul’s letter to the Romans for that matter. Just be ready to share how your faith guides your life before God. Share what it means to be a true follower of Jesus and do so “with gentleness and reverence.” In living this way, one emulates Jesus, who suffered on our account, “the righteous one on behalf of the righteous. He did this to bring you into the presence of God” (1 Peter 3:18 CEB).

What begins as a call to emulate Jesus moves off into a conversation about the fullness of Jesus’ vindication. Though Jesus suffered, that is not the final verdict. Before he is fully resurrected and has ascended into the heavens taking his rightful place at God’s right hand, he takes a major detour. As verse 19 suggests (this is an intriguing verse that can lead to several possible interpretations) Jesus preached to the spirits in prison, primarily those who had disobeyed at the time of Noah. This verse gave rise to the idea that in that interim between burial and resurrection, Jesus descended to Hades and preached there. This is called the “harrowing of hell.” It is a perspective that had wide usage in the ancient church. It’s one of those passages that is suggestive, but not conclusive. Though it did find its way into the Apostles Creed. The point that Peter makes here is that those who had disobeyed had an opportunity to repent and be restored to life in the resurrection.

Before moving to the resurrection, Peter uses the story of Noah and his family as a prefigurement of baptism. Just as they were saved from judgment through water, now we are saved through baptism, “not as a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ” (1 Pet. 3:21). In other words, this isn’t a magical act. It is a turning to the risen Christ and finding salvation in his resurrection and ascension.

This leads back to the beginning, which is the call to live faithfully in the face of suffering. There is a rather pragmatic view in place, which suggests that if we do what is right then a difficult situation might become less difficult, or at least not become more difficult than it already is. Regarding slaves and wives, if they are Christians and their masters/husbands are not, they could be in for a difficult situation. So, there is a degree of pragmatism at work here. As Scot McKnight puts it:

His optimistic hope about the value of doing good is tempered by a genuine realism, for in several places he suggests the likelihood of being persecuted. Thus, it is important that his pragmatic argument not be given too much weight in his overall strategy for living Christianly in the world. But the argument is nonetheless valid: If we assume (1) the similarity of human nature and (2) the general limitation of such an argument, then it becomes important to urge Christians who are being persecuted to live godly and good lives so that those who are against them might be more tolerant of them. That is, human beings in general do appreciate being respected, and when they are respected, they will be kinder. [McKnight, 1Peter (The NIV Application Commentary Book 17) (pp. 218-219). Zondervan Academic. Kindle Edition.]

Peter isn’t a radical. He’s pragmatic, but he is also faithful. So, as we read him, it’s important to remember that different contexts require different responses. Nevertheless, we are called to live faithfully, and so far as it is possible, we shouldn’t give offense to our neighbors. So, in the context in which we find ourselves right now, wearing a mask, use physical distancing, and follow the government guidelines is a good witness. It isn’t about my right to do as I please. It is about the call to love my neighbor by caring for their needs. By doing this we express our baptismal confession in the risen and ascended Christ.

| Image attribution: Ermakova, Natalia. Noah’s Ark Icon, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=56487 [retrieved May 9, 2020]. Original source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jimforest/4338027250/ – Jim Forest. |