1 Thessalonians 2:9-20 New Revised Standard Version

9 You remember our labor and toil, brothers and sisters; we worked night and day, so that we might not burden any of you while we proclaimed to you the gospel of God. 10 You are witnesses, and God also, how pure, upright, and blameless our conduct was toward you believers. 11 As you know, we dealt with each one of you like a father with his children, 12 urging and encouraging you and pleading that you lead a life worthy of God, who calls you into his own kingdom and glory.

13 We also constantly give thanks to God for this, that when you received the word of God that you heard from us, you accepted it not as a human word but as what it really is, God’s word, which is also at work in you believers. 14 For you, brothers and sisters, became imitators of the churches of God in Christ Jesus that are in Judea, for you suffered the same things from your own compatriots as they did from the Jews, 15 who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out; they displease God and oppose everyone 16 by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles so that they may be saved. Thus, they have

constantly been filling up the measure of their sins; but God’s wrath has

overtaken them at last.17 As for us, brothers and sisters, when, for a short time, we were made orphans by being separated from you—in person, not in heart—we longed with great eagerness to see you face to face. 18 For we wanted to come to you—certainly I, Paul, wanted to again and again—but Satan blocked our way. 19 For what is our hope or joy or crown of boasting before our Lord Jesus at his coming? Is it not you? 20 Yes, you are our glory and joy!

****************

Paul speaks to the Thessalonians as a father speaks to his children (vs. 11). What we are tasked by the Lectionary to read/reflect upon here (vs. 9-13) is a continuation of the reading from the previous week, where Paul revealed that God had entrusted the gospel to them (Paul and companions). Thus, the reading here reinforces the earlier message concerning their mission in Thessalonica and beyond. Paul affirms their being witnesses, along with God, of the diligence with which Paul and his companions proclaimed the Gospel in Thessalonica. As noted in the opening verses of the chapter, Paul reminded them that he and his companions hadn’t proclaimed the gospel with false motives or out of concern for financial gain. They didn’t even take advantage of their rights as apostles (vs. 5-7). In other words, they weren’t hirelings. They were servants of God’s mission in the world.

As noted, the Revised Common Lectionary limits the reading for the week to verses 9-13. It’s understandable that verses 14-16 are omitted (there are unfortunate words regarding the Jews), but it seemed to be important to take a look at the remainder of the chapter to better understand Paul’s words here in verses 9-13.

The centerpiece of this week’s reading is the nature of the Gospel proclamation. Paul commends the Thessalonians for receiving their message not as a human word, but as the word of God. In describing their message as a divine rather than human word, Paul isn’t implying that their message was somehow inerrant or infallible (these categories are rather modern and thus not something Paul would have even considered). Rather they were speaking to their belief that God’s word had been made known in Thessalonica through their ministry. In other words, God speaks through human voices and words. There is good news here. The word has been heard and embraced by some (that’s the locus of the selected reading), but there is also opposition (the remainder of the chapter). Both exist and must be addressed. In the end, however, Paul commends them as being his crown when Jesus returns.

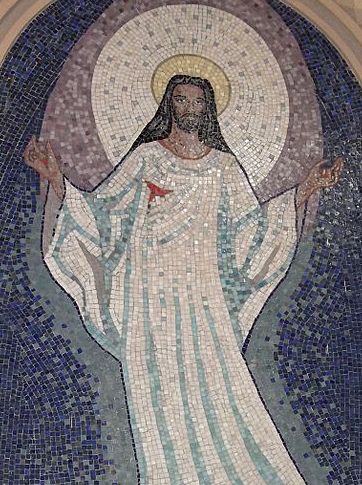

The concept of the “word of God” is problematic. That’s because too often this phrase is applied solely to Scripture, when in fact the phrase is used in multiple ways. First and foremost, the term Word (Gk. Logos) is used in reference to Jesus, who is understood to be the Word (Logos) of God incarnate (Jn.1:1-14). In several places in the Book of Acts, the phrase is used in terms of the proclamation of the Gospel. That is the case here, where Paul has in mind the act of preaching/proclamation. The variety of ways this phrased is used has led me to embrace Karl Barth’s well-known articulation of the principle of the “three-fold Word of God.” As I’ve noted in a book on this question, Barth has proven very helpful in my own theological journey. Barth writes in the first volume of his Church Dogmatics

Proclamation is human speech in and by which God Himself speaks like a king through the mouth of his herald, and which is meant to be heard and accepted as speech in and by which God Himself speaks, and therefore heard and accepted in faith as divine decision concerning life and death, as divine judgment and pardon, eternal Law and eternal Gospel both together. [Church Dogmatics, 1:1:52].

Of course, Barth, and I assume Paul would agree, recognizes that not all preaching reflects God’s message. However, both men recognize that God can speak through human messengers, and thus preaching can be a conduit of God’s word.

Having made this clear, speaking as a father to his children, Paul urges the readers to live lives worthy of God, “who calls you into his own kingdom and glory” (vs. 12). This is a good place to pause and note that while Paul places great emphasis on God’s grace received by faith, he is also concerned about conduct (behavior), which might be understood as works. Therefore, he gives thanks that the Thessalonians received their word as the word of God and that this word is at work in their midst.

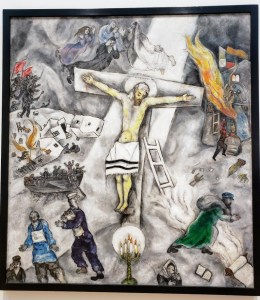

Having taken note of this gracious word on Paul’s part, we now must take note of a most problematic word concerning the Jews. In verses 14-16 Paul commends them for being imitators of the churches in Judea who had suffered persecution from “the Jews,” even as they were suffering similarly. We need to remember that contextually Paul understands his message being directed at reaching Gentiles. He finds any interference in that work problematic (at the very least). This leads to an unfortunate rebuke of his fellow Jews, who had opposed the Churches in Judea and had done the same in Thessalonica. If we remember that this letter was written several decades before the Book of Acts, we might want to take note of Acts 17, where Luke tells us of Paul and Silas’ visit to Thessalonica. In that passage, Paul is said to go and preach in the synagogue concerning Jesus. While some followed Paul, along with devout Greeks and leading women, “the Jews became jealous,” and along with some ruffians in the community attacked Jason for hosting them. That led Paul to head off to Berea and then Athens. This might be what Paul is referring to, but we can’t be certain.

Living in a post-Shoah world, where the murder of millions of Jews along with others, has forced the church to be attentive to texts that have been and can be used to justify persecution and even murder of Jews. In a sidebar in the Jewish Annotated New Testament, we read this reminder: “These verses present a succinct summary of classical Christian anti-Judaism: the Jews killed Jesus, persecuted his followers, and threw them out of the synagogues; they are xenophobic and sinners, and God has rejected and punished them. The harshness of these words raises questions about Paul’s attitude toward his fellow Jews” [Jewish Annotated New Testament, p. 374].

There have been suggestions among scholars that this sounds less like Paul and more like a later Gentile scribal insertion. While that makes some sense, especially since it doesn’t fit well with what Paul writes in Romans 9-11, where he affirms that God has not rejected the Jewish people. The problem with this suggestion is that there is no textual support for such a conclusion. In any case, whether these are Paul’s words or not, unfortunately, the damage has been done and the passage can be and has been used to justify anti-Jewish views and behavior. It would seem that Paul is trying to encourage his spiritual children to persevere in the face of

opposition and even persecution. Contextually, this might be understandable when one is in a minority position. However, in a different context, when Jews are the minority voice, this can be dangerous.

Having commended them for hearing and embracing their message as God’s word to them, and having encouraged them as they experience persecution, the chapter closes with Paul letting the community know that he wants to visit them. Unfortunately, Satan had blocked their way time and again. The reference to Satan’s interference reminds us that Paul viewed the world in supernaturalist/apocalyptic terms. As John Byron notes: “Although Paul does not explain what Satan did to hinder him, he has an acute sense that his freedom of movement was curtailed, and viewing the situation on a supernatural level, determined that Satan was interfering with the seen world.” [Benjamin E. Reynolds. The Jewish Apocalyptic Tradition and the Shaping of New Testament Thought (p. 249). Fortress Press. Kindle Edition]. Despite the supernatural interference (however that transpired), Paul celebrates their faith. They are his hope and joy, and the “crown of boasting before our Lord Jesus at his coming.” That is, when Jesus comes in his glory to judge the living and the dead, Paul can stand before Jesus and point to them as being his crown of glory and joy!